Twelve Crore voters, if they decide to vote similarly, would determine the fate of India in 2014. Yes, as low as less than 10% of India’s total population hold the key to the future of a nation of more than 1.25 billion people. Such is the mathematical construct of our Westminster system of first-past-the-post democracy that a political party can rule this country by just about managing to get 12 Cr votes. Yet every day we get to hear such banal intellectual discourse based around secular definitions of Majority and Minority. In the real world of Indian elections, the ultimate minorities are the group of voters who actually end up electing a government!

This figure of 12 Cr is absolutely the key to getting anywhere beyond the 200 mark for any single political party in 2014. Current estimates suggest that a total of 73 Crore voters would be eligible to participate in the 2014 elections. Assuming a voter turnout of roughly 60% or about 44 Cr, either of the two national parties; Congress and the BJP; should get closer to about 12 Cr votes if a stable government is to be formed. Past electoral data suggests that stable Congress governments of the last 3 decades have always been possible when the party has been closer to the 12 Cr mark. Although the two BJP led governments of 1998 and 1999 came at a much lower threshold of about 9 Cr votes and 180 LS seats, the party would need to touch the same 12 Cr mark to have a safe mandate in 2014. If either of the two national parties’ fail to get close to 12 Cr votes, then 2014 would see a fragmented verdict wherein the third and fourth front space would then be open to temporary maneuvers. Thus at the outset, looking at the past voting data, the path for Congress to retain about 12 Cr votes should be much easier than say for the BJP to accrue 4 Cr more votes in 2009. But the electoral landscape in India is neither so simple nor so straightforward.

This figure of 12 Cr is absolutely the key to getting anywhere beyond the 200 mark for any single political party in 2014. Current estimates suggest that a total of 73 Crore voters would be eligible to participate in the 2014 elections. Assuming a voter turnout of roughly 60% or about 44 Cr, either of the two national parties; Congress and the BJP; should get closer to about 12 Cr votes if a stable government is to be formed. Past electoral data suggests that stable Congress governments of the last 3 decades have always been possible when the party has been closer to the 12 Cr mark. Although the two BJP led governments of 1998 and 1999 came at a much lower threshold of about 9 Cr votes and 180 LS seats, the party would need to touch the same 12 Cr mark to have a safe mandate in 2014. If either of the two national parties’ fail to get close to 12 Cr votes, then 2014 would see a fragmented verdict wherein the third and fourth front space would then be open to temporary maneuvers. Thus at the outset, looking at the past voting data, the path for Congress to retain about 12 Cr votes should be much easier than say for the BJP to accrue 4 Cr more votes in 2009. But the electoral landscape in India is neither so simple nor so straightforward.

In order to understand how exactly the 2014 election is likely to shape, 5Forty3 has decided to release the 2014 electoral map, a first of its kind exercise in the Indian election arena which will help us gauge the direction of different political undercurrents. For the express purpose of 2014, India can be classified into three zones – The Heartland Zone, The Southern Hemisphere and East India.

These three zones of the electoral chessboard of India represent the three political quadrants; The Heartland Zone dominated by BJP, The Southern Hemisphere being the Congress citadel and East India representing the third political force of India. Of course there will be minor zonal overlaps, but in broad electoral strokes this chessboard holds good. Each of the political force has to hold on to its quadrant and try to penetrate the enemy zone to win the battleground of 2014.

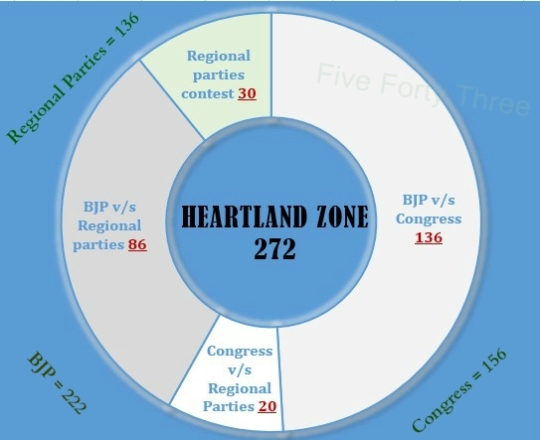

Heartland Zone

The Heartland Zone is essentially what is referred to as North India plus Gujarat. This is the region where BJP has been strong traditionally and Congress has been in almost terminal decline since the 90s. In fact, Congress is in power in only 4 small states accounting for a paltry 25 out of 272 LS seats (less than 10%) of this region. BJP, on the other hand, has won 4 major states (including Gujarat as of December 2012) in the last one year and is experiencing a general upswing in the entire region. In the run-up to the 2014 polls, The Heartland Zone is one geography where there is a massive anti-incumbency against the central government as witnessed in the recently concluded assembly elections of four states in which the Congress party was almost completely whitewashed. This is also the region where the NaMo wave is at its strongest as we have seen time and again in his hugely successful public meetings attended by almost unprecedented crowds.

Out of the 272 parliamentary seats in the heartland zone about 136 will witness a direct fight between the two national parties, in 86 seats BJP is fighting against the regional parties and Congress is contesting the regional parties in about 20 seats while there are 30 seats where both Congress and BJP are both not in contest. Essentially, Congress has a pool of 156 MP seats, BJP has 222 and regional parties have a maximum pool of 136 MP seats to win from.

Out of the 272 parliamentary seats in the heartland zone about 136 will witness a direct fight between the two national parties, in 86 seats BJP is fighting against the regional parties and Congress is contesting the regional parties in about 20 seats while there are 30 seats where both Congress and BJP are both not in contest. Essentially, Congress has a pool of 156 MP seats, BJP has 222 and regional parties have a maximum pool of 136 MP seats to win from.

The advantage for BJP is obviously due to the larger pool of LS seats it has to choose from, but the problem for the party is that this is the zone from where close to 75% of the party MPs would be coming from, so it needs a huge success ratio of practically winning 3 out of 4 seats it is contesting. Congress, which had performed reasonably well in this region in 2009 is staring at a complete rout, but the advantage for the party lies in its increasing insignificance in heartland which gives it tremendous flexibility to pick up regional allies. Regional parties throw the biggest challenge to BJP in this zone, except in Punjab and Haryana where they are in a symbiotic relationship with the party.

BJP: In 2014, BJP needs a vote swing of 6 to 9% in its favor to achieve its target of winning 3 out of 4 seats that it is seriously contesting. Will Narendra Modi be able to bring such a major swing in this region? Going by the results of the recently concluded assembly elections, he seems to be on course to achieve this but has a huge task of getting the local flavours right. North India usually has a latent national vote in the LS elections (as was witnessed last time in 2009 when Congress performed beyond its means), which should help Modi and BJP in a classical sense. The key factor for the party would be its battle for the OBC votes with regional parties to create a united spectrum of Hindu vote. The other important factor for the party is how well it is able to sell its “good governance model” to the impoverished voters of the heartland. Its big worry is a united opposition.

Congress: The party is definitely losing 5%+ vote share in this region, but it needs to spread that lost vote-share wisely by allying with regional parties. Congress party has two aces up its sleeve – 1) to prime its MAD – Muslim-Adivasi-Dalit coalition and 2) try and ally with as many regional parties as possible. Its biggest drawback is the 10 year anti-incumbency and all the public anger as a result of huge corruption scams and economic mismanagement manifesting into high inflation. In the heartland, Congress should fight the election not to win, because it cannot win in any case, but to limit BJP’s margins, so it has to find allies at any cost. To a large extent, BJP’s performance in the heartland will depend on how well Congress manages the regional parties.

Regional Parties: The obvious dichotomy of different state level regional parties is the biggest stumbling block for them to put up a united face; SP-BSP, JDU-RJD, JMM-JVM etc. The combined vote-share of the regional parties may marginally decline by 1 or 2% as has been evident in the recently concluded assembly elections in the four states, but even if they manage to increase the vote-share it would be essentially redistributed amongst themselves and from the unattached vote-share. The key for the regional parties in heartland is to either form a front to prove their relevance to the national elections or to align with one of the national parties. This is one of the primary reasons why Mayawati is even considering to have an alliance with the Congress party, for the regional parties of the heartland have now discovered that there is a powerful “national vote” in the region which has gained greater weightage in 2014 as compared to 2009.

Key battleground elements: 1) The national vote, 2) Narendra Modi and 3) Anti-BJP alliances

Southern Hemisphere

The Southern Hemisphere is essentially South India plus Maharashtra and is generically classified as the Congress quadrant, for this has been a traditional Congress stronghold. Now the southern hemisphere is completely fragmented among various small regional and sub-regional political parties due to the general decline of the Congress party. BJP has limited presence in this region and needs alliances to leverage the popularity of its prime ministerial candidate, Narendra Modi. The major contests in this region are among regional parties of the third and fourth fronts, which is manifested in the fact that both the national parties are in a direct contest only in 47 of the 182 seats. This is the one region where a maximum number of seats see multi-cornered fights due to political fragmentation.

The Southern Hemisphere is essentially South India plus Maharashtra and is generically classified as the Congress quadrant, for this has been a traditional Congress stronghold. Now the southern hemisphere is completely fragmented among various small regional and sub-regional political parties due to the general decline of the Congress party. BJP has limited presence in this region and needs alliances to leverage the popularity of its prime ministerial candidate, Narendra Modi. The major contests in this region are among regional parties of the third and fourth fronts, which is manifested in the fact that both the national parties are in a direct contest only in 47 of the 182 seats. This is the one region where a maximum number of seats see multi-cornered fights due to political fragmentation.

Congress and UPA: The Congress party had a huge 15% lead over its nearest rival in this region in 2009, but this time in 2014, Congress is in a precarious situation due to a split in the party and the collapse of an alliance. There is a real possibility of a 6 to 9% swing away from the Congress party which could potentially bring the total tally of Congress MPs in the 16th Lok Sabha perilously close to the double digit mark. The party has a very difficult task of bridging alliances and building new coalitions to stay afloat in South India. Keeping UPA intact in Maharashtra and rebuilding UPA in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh are the twin challenges that Congress is facing in the run-up to 2014. The party’s performance would be largely decided by how it manages to overcome these two challenges. Congress and UPA need to get anywhere between 70 to 90 seats in this region to have a realistic shot at government formation in 2014, or else a long spell on the opposition benches awaits them.

BJP and NDA: BJP has always been a North Indian party and only has pockets of influence in this region. The best chance for the party to have an impact outside its strength areas is to try and contest the metro-urban LS seats by leveraging brand NaMo and using the AAP model of volunteers, especially of the internet variety. BJP needs to retain its vote-share of around 15% here, but may find it very difficult to repeat Karnataka of 2009. Getting the NDA quotient right in AP, TN and Maharashtra is going to be extremely crucial for the eventual BJP performance and it would also test the skills of Narendra Modi as an alliance builder. The challenge for the BJP-NDA would be about offsetting the obvious losses in Karnataka by winning elsewhere in south India.

Third Front & Fourth Front: These are loose terms used for various political groupings that are amorphous in nature and keep changing in contours with the passage of time. As of now third front consists of the Left, ADMK, JDS and YSRC etc., whereas the Fourth Front is composed of DMK, DMDK, TRS and others. Together these two fronts commanded a respectable 21% vote-share in the 2009 elections and may increase that substantially this time due to a swing away from the Congress party. Even in terms of seats, these groupings are likely to emerge with the largest haul of MPs from South India in the 16th Lok Sabha. This is the big contradiction of today; while the fragmented north Indian polity is stabilizing, the earlier stable south Indian polity is splitting up. Unlike North India, southern hemisphere doesn’t have a “national vote” even in the LS polls and witnesses localized elections along different sub-regional fault lines.

Key Battleground Elements: 1) The shape of UPA & NDA, 2) The resolution of inter-party contradictions among different fronts and 3) BJP-NDA’s ability to leverage brand Narendra Modi

East India

East India, composed of Orissa, West Bengal and the seven sisters of North-East, is a region where both the national parties are absent from vast swathes of geography and is dominated by regional players and the third front. The third and fourth fronts have a big pool of 71 out of 89 MP seats to win from, whereas Congress has 52 and BJP a paltry 11 seats from where it can emerge victorious. East India is also unique in the fact that caste based voting blocks are much less prevalent if not non-existent in this part of the country unlike the other two zones. Another trait that East India shares with the Southern Hemisphere is the absence of a “national vote” and instead it votes on regional, sub-regional aspirations and differentiations. Congress brand of politics used to provide the alternate platform for the national vote in this part of India but it is again in secular decline across the region, while Left-Front has also lost a lot of ground as the third pole of Indian politics. Thus 2014 is likely to be dominated by a regional vote in East India.

East India, composed of Orissa, West Bengal and the seven sisters of North-East, is a region where both the national parties are absent from vast swathes of geography and is dominated by regional players and the third front. The third and fourth fronts have a big pool of 71 out of 89 MP seats to win from, whereas Congress has 52 and BJP a paltry 11 seats from where it can emerge victorious. East India is also unique in the fact that caste based voting blocks are much less prevalent if not non-existent in this part of the country unlike the other two zones. Another trait that East India shares with the Southern Hemisphere is the absence of a “national vote” and instead it votes on regional, sub-regional aspirations and differentiations. Congress brand of politics used to provide the alternate platform for the national vote in this part of India but it is again in secular decline across the region, while Left-Front has also lost a lot of ground as the third pole of Indian politics. Thus 2014 is likely to be dominated by a regional vote in East India.

Third Front: Mainly constituted by the Left, BJD and other smaller players of North East, this grouping had a massive 11% lead over its nearest rival in 2009. This time the Third Front is likely to see a 3-5% swing away from it mainly due to the decline of the left and only partially due to the BJD’s anti-incumbency. The Third Front is a strong contender in about 63 seats here and would be lucky if it could win closer to 50% of those.

Congress: May spring a surprise in this region by producing a contrarian result from rest of India. Although the party is now on a weaker wicket in West Bengal, it seems to be in an upswing in Orissa (especially among Adivasi & Dalit votes) and ahead of the pack in Assam. There is a possibility of an overall 1-2% swing in favor of the party in this region despite loss of vote-share in WB. Come 2014, this could be the one saving grace for a beleaguered Congress party leadership.

Fourth Front: This is mainly formed by Trinamool Congress (TC) which cannot go with either the Left or the Congress in 2014, but we have also added the Vote-Share of AUDF to this block. It is generally expected to gain a 2-3% swing in its favor in 2014 and perform reasonably well. The amorphous nature of Fourth Front gives it post-poll flexibility but faces restrictions in the pre-poll scenario due to inherent regional contradictions and the risk of antagonizing vote-banks.

BJP-NDA: BJP has very limited presence in this region and also very few possibilities of forming formidable alliances. The two possible NDA allies are AGP and a Sangma led NCP; BJP’s performance in this region largely depends on how it can create an NDA with these two allies. In any case, whatever the party or the alliance wins here would be a bonus, for this is one region where Narendra Modi may have no impact whatsoever.

Key Battleground Elements: 1) The Muslim and Adivasi vote, 2) The extent of decline of the Left and 3) The redrawing of Hindu-Muslim fault lines after Assam riots

[P.S: These numbers are true as of today and will be updated in the run-up to 2014 as and when ground situations keep developing]

In the next part we will further divide these three zones into 7 territories in order to have a more deeper analysis of the unfolding electoral scenario and also make projections for different territories based on a unique survey experiment conducted for the first time in India.